I want to watch the computer play a game with itself. So I pick the easiest game, tic-tac-toe, and see how well the computer can play. Tic-tac-toe is never an interesting game. Any sensible human playing it will make a draw. So if computer is smart enough, it should also make a draw.

Skeleton of self-play engine

We start with the skeleton. A game that computer play against itself is simpler as I do not need to implement the user interface to obtain human input. So this will be a very simple loop:

def play():

game = Board()

player = 'X'

while not game.won():

opponent = 'O' if player == 'X' else 'X'

game = move(game, player)

print("%s move:" % player)

print(game)

player = opponent

winner = game.won()

print()

if not winner:

print("Tied")

else:

print("%s has won" % winner)

But now we need to create a board representation, and some checker to verify the game is over. To keep the board position, we can simply use a 2D array. To check whether we have a winner, we need to check all possibilities of a tic-tac-toe winning. And to determine if there is a tie, we need to verify that the board is full. So here is the board class:

import copy

class Board:

"""simple tic-tac-toe board"""

def __init__(self, board=None):

if board:

self.board = copy.deepcopy(board)

else:

self.board = [[' '] * 3 for _ in range(3)]

def place(self, row, col, what):

"""produce a new board with row and col set to a symbol. Return None if

some symbol already set."""

if self.board[row][col] == ' ':

newboard = Board(self.board)

newboard[row][col] = what

return newboard

def __getitem__(self, key):

return self.board[key]

def __repr__(self):

separator = "\n---+---+---\n "

return " " + separator.join([" | ".join(row) for row in self.board])

def spaces(self):

"""tell how many empty spots on the board"""

return sum(1 for i in range(3) for j in range(3) if self[i][j] == ' ')

def won(self):

"""check winner. Return the winner's symbol or None"""

# check rows

for row in self.board:

if row[0] != ' ' and all(c==row[0] for c in row):

return row[0]

# check cols

for n in range(3):

if self.board[0][n] != ' ' and all(self.board[i][n] == self.board[0][n] for i in range(3)):

return self.board[0][n]

# check diag

if self.board[0][0] != ' ' and all(self.board[n][n] == self.board[0][0] for n in range(3)):

return self.board[0][0]

if self.board[0][2] != ' ' and all(self.board[n][2-n] == self.board[0][2] for n in range(3)):

return self.board[0][2]

We can now verify the board works by making a human playing game:

def play():

"auto play tic-tac-toe"

game = Board()

player = 'X'

# loop until the game is done

print(game)

while not game.won():

opponent = 'O' if player == 'X' else 'X'

while True:

userin = input("Player %s, input coordinate (0-2, 0-2):" % player)

nums = "".join(c if c.isdigit() else ' ' for c in userin).split()

if len(nums) != 2:

continue

nums = [int(n) for n in nums]

if not all(0 <= n <= 2 for n in nums):

continue

nextstep = game.place(nums[0], nums[1], player)

if nextstep:

game = nextstep

break

print()

print("%s move:" % player)

print(game)

player = opponent

winner = game.won()

print()

if not winner:

print("Tied")

else:

print("%s has won" % winner)

and we can see it really works:

| |

---+---+---

| |

---+---+---

| |

Player X, input coordinate (0-2, 0-2):1,1

X move:

| |

---+---+---

| X |

---+---+---

| |

Player O, input coordinate (0-2, 0-2):1,1

Player O, input coordinate (0-2, 0-2):0,2

O move:

| | O

---+---+---

| X |

---+---+---

| |

Player X, input coordinate (0-2, 0-2):0,3

Player X, input coordinate (0-2, 0-2):1,2

X move:

| | O

---+---+---

| X | X

---+---+---

| |

Player O, input coordinate (0-2, 0-2):0,0

O move:

O | | O

---+---+---

| X | X

---+---+---

| |

Player X, input coordinate (0-2, 0-2):1,0

X move:

O | | O

---+---+---

X | X | X

---+---+---

| |

X has won

First step of AI: Game tree search

The old school way of doing AI on such board game is to do a game tree search. The board class above actually prepared for that. Imagine we have a position and now is a particular player’s turn. All possible positions can be generated as follows:

next_steps = filter(None, [game.place(r, c, player) for r in range(3) for c in range(3)])

This will contain only the legitimate next step positions, i.e., we place at a empty box only. Recursively we do this for each position, we generated a game tree, with a depth of 9 (because we have 9 spots to play). Below is an illustration from Wikipedia:

The goal of playing the game is to win. If we at the leaf nodes of the tree, we can determine if a player has won, lost, or it is a draw. So basically we can make a evaluation function to score the state of the end game:

def evaluate(board):

"""simple evaluator: +10, -10 for someone won, 0 for tie, None for all other"""

winner = board.won()

if winner == "X":

return 10

elif winner == "O":

return -10

if not board.spaces():

return 0

Now we move on to the core of searching the game tree. The idea is that every player will play to her advantage. If there are two moves that one is sure to loss, the player must avoid it. It will be trivial if it is one level above a leaf node of the game tree. Thus at that level, we can find the worst possible outcome and the player suppose to minimize the worst possible score. Then we have the minimax algorithm: At each turn, players are to minimize the maximum loss. And the loss is computed recursively until the leaf node. So here we have our code:

COUNT = 0

PLAYERS = ["X", "O"]

def minimax(board, player):

"""player to move one step on the board, find the minimax (best of the worse case) score"""

global COUNT

COUNT += 1

opponent = "O" if player == "X" else "X"

value = evaluate(board)

if value is not None:

return value # exact score of the board, at leaf node

# possible opponent moves: The worse case scores in different options

candscores = [minimax(b, opponent) for b in [board.place(r, c, player) for r in range(3) for c in range(3)] if b]

# evaluate the best of worse case scores

if player == "X":

return max(candscores)

else:

return min(candscores)

def play():

"auto play tic-tac-toe"

global COUNT

minimizer = True

game = Board()

# loop until the game is done

while not game.won():

player = PLAYERS[minimizer]

opponent = PLAYERS[not minimizer]

COUNT = 0

candidates = [(b, minimax(b, opponent)) for b in [game.place(r, c, player) for r in range(3) for c in range(3)] if b]

if not candidates:

break

random.shuffle(candidates)

# find best move: optimizing the worse case score

if player == "X":

game = max(candidates, key=lambda pair: pair[1])[0]

else:

game = min(candidates, key=lambda pair: pair[1])[0]

# print board and switch

minimizer = not minimizer

print()

print("%s move after %d search steps:" % (player, COUNT))

print(game)

winner = game.won()

print()

if not winner:

print("Tied")

else:

print("%s has won" % winner)

We defined the evaluation function in such a way that “X” win will have a positive score and “O” win will have a negative score. Therefore player “X” will try to maximize the score while player “O” will try to minimize it. Hence we call them the maximizer and minimizer respectively and the node on the game tree that player “X” to move the maximizer node and the otherwise the minimizer node.

In the functions above, the maximizer is to maximize the potential score among

all possible next steps, and vice versa. The function minimax() is to find

such minimax score of a player. So when it is the maximizer, we compute the

minimax score of the minimizer on each next step positions. The minimax()

function in turn, compute using the next step positions of the minimizer and

recursively in a similar fashion until the leaf nodes. The game in this form

goes like the following:

O move after 549945 search steps:

| |

---+---+---

| | O

---+---+---

| |

X move after 63904 search steps:

| | X

---+---+---

| | O

---+---+---

| |

O move after 8751 search steps:

| | X

---+---+---

| | O

---+---+---

O | |

X move after 1456 search steps:

X | | X

---+---+---

| | O

---+---+---

O | |

O move after 205 search steps:

X | O | X

---+---+---

| | O

---+---+---

O | |

X move after 60 search steps:

X | O | X

---+---+---

| X | O

---+---+---

O | |

O move after 13 search steps:

X | O | X

---+---+---

| X | O

---+---+---

O | | O

X move after 4 search steps:

X | O | X

---+---+---

| X | O

---+---+---

O | X | O

O move after 1 search steps:

X | O | X

---+---+---

O | X | O

---+---+---

O | X | O

Tied

The code above intentionally keep a counter COUNT to see how efficient the

game will be. And we randomize the possible moves at each step to work around

the issue of multiple possible next steps having same minimax score. Indeed,

the game in this form is really slow. One way to see it, a tic-tac-toe game has

9 boxes and each box can either be “X”, “O”, or blank. So there can only be

\(3^9 = 19683\) possible positions on the board. But we searched 549945

positions on the first move. This is because we searched a lot of duplicated

positions — as the same position can be reached by different combination of

moves, and the nodes on the game tree have a lot of repetitions.

Alpha-beta pruning

The game tree of a game as simple as tic-tac-toe can have orders of magnitude more nodes than the possible positions in the game. If we work on a more complicated game, the game tree can easily go intractable. Therefore, we should avoid searching the whole game tree.

Half a century ago, people invented the alpha-beta pruning algorithm to avoid the part of the game tree that is know to be not interesting. The idea is not hard to understand: Imagine it is on a maximizer node, and we have a number of possible next moves. We check one by one for the minimax score and get some idea of what we can do. So on the first next move, we evaluate the minimax score on behalf of a minimizer. On the second next move, we expect a higher score than what we got from the previous evaluation. However, as a minimizer, it will prefer the lower score. So we can let the minimax function know that whenever we find the minimizer saw an option of score lower than this previous score, we can stop (prune the game tree) on this minimizer node – since this minimizer node will never be an option for the maximizer node one level above. Similar idea for searching on a minimizer node. Recursively on this idea, we have the alpha-beta search.

Implementing this idea:

def alphabeta(board, player, alpha=-float("inf"), beta=float("inf")):

"""minimax with alpha-beta pruning. It implies that we expect the score

should between lowerbound alpha and upperbound beta to be useful

"""

global COUNT

COUNT += 1

opponent = "O" if player == "X" else "X"

value = evaluate(board)

if value is not None:

return value # exact score of the board (terminal nodes)

# minimax search with alpha-beta pruning

children = filter(None, [board.place(r, c, player) for r in range(3) for c in range(3)])

if player == "X": # player is maximizer

value = -float("inf")

for child in children:

value = max(value, alphabeta(child, opponent, alpha, beta))

alpha = max(alpha, value)

if alpha >= beta:

break # beta cut-off

else: # player is minimizer

value = float("inf")

for child in children:

value = min(value, alphabeta(child, opponent, alpha, beta))

beta = min(beta, value)

if alpha >= beta:

break # alpha cut-off

return value

As a convention, we call the lower bound and upper bound of the minimax score as we learned so far as \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) respectively. They are initially at negative and positive infinity and narrowed down as the alpha-beta search proceeds – we move up the lower bound on maximizer nodes and move down the upper bound on minimizer nodes, as this is the idea of what minimax is about. Whenever we have \(\alpha \gt \beta\), we can prune the branch. We call the pruning at maximizer node the beta cut-off and the one at minimizer node the alpha cut-off.

Running this to replace the previous minimax() function will be much faster,

as less nodes are searched:

O move after 30709 search steps:

| |

---+---+---

| | O

---+---+---

| |

X move after 9785 search steps:

| | X

---+---+---

| | O

---+---+---

| |

O move after 1589 search steps:

| | X

---+---+---

| | O

---+---+---

O | |

X move after 560 search steps:

X | | X

---+---+---

| | O

---+---+---

O | |

O move after 121 search steps:

X | O | X

---+---+---

| | O

---+---+---

O | |

X move after 53 search steps:

X | O | X

---+---+---

| X | O

---+---+---

O | |

O move after 13 search steps:

X | O | X

---+---+---

| X | O

---+---+---

O | | O

X move after 4 search steps:

X | O | X

---+---+---

| X | O

---+---+---

O | X | O

O move after 1 search steps:

X | O | X

---+---+---

O | X | O

---+---+---

O | X | O

Tied

Performance improvement

There are a few areas we can improve the program to make it faster.

Firstly, we modify the Board class, as below. It will be very useful later.

We do not want to use 2D array any more. Instead, we use a bitboard – using a

bit vector to represent the board position. As there are two players and nine

boxes, we can use 18 bits to represent all positions, the 9 MSB for player “X”

and the 9 LSB for player “O”. It will be less convenient when we want to mark a

box but in return, handing a single integer is much faster than a 2D array.

Secondly, we use +1 and -1 instead of “X” and “O” in the code as we are now using bitboard. We convert them into symbols only when we need to print it. The benefit of this is that we are now easier to distinguish maximizer and minimizer – by comparing the sign.

from gmpy import popcount

PLAYERS = [1, -1] # maximizer == 1

COORDS = [(r,c) for r in range(3) for c in range(3)]

def symbol(code):

"""Return the symbol of player"""

assert code in PLAYERS

return "X" if code == 1 else "O"

def grouper(iterable, n, fillvalue=None):

# https://docs.python.org/3.7/library/itertools.html

args = [iter(iterable)] * n

return itertools.zip_longest(*args, fillvalue=fillvalue)

class Board:

"""bit-vector based tic-tac-toe board"""

def __init__(self, board=0):

self.board = board

def mask(self, row, col, who):

"""Produce the bitmask for row and col

The 18-bit vector is row-major, with matrix cell (0,0) the MSB. And the

higher 9-bit is for 1 (X) and lower 9-bit is for -1 (O)

Args:

row, col: integers from 0 to 2 inclusive

"""

offset = 3*(2-row) + (2-col)

if who == 1:

offset += 9

return 1 << offset

def place(self, row, col, what: int):

"""produce a new board with row and col set to a symbol. Return None if

some symbol already set.

Args:

what: either +1 or -1

"""

assert what in PLAYERS

mask = self.mask(row, col, what)

checkmask = self.mask(row, col, -what)

if (mask | checkmask) & self.board:

return None # something already on this box

return Board(self.board | mask)

def __repr__(self):

def emit():

omask = 1 << 8

xmask = omask << 9

while omask: # until the mask becomes zero

yield "O" if self.board & omask else "X" if self.board & xmask else " "

omask >>= 1

xmask >>= 1

separator = "\n---+---+---\n "

return " " + separator.join(" | ".join(g) for g in grouper(emit(), 3))

def spaces(self):

"""tell how many empty spots on the board"""

# alternative if no gmpy: bit(self.board).count("1")

return 9 - popcount(self.board)

masks = (0b000000111, 0b000111000, 0b111000000, # rows

0b001001001, 0b010010010, 0b100100100, # cols

0b100010001, 0b001010100 # diags

)

def won(self):

"""check winner. Return the winner's symbol or None"""

shifted = self.board >> 9

for mask in self.masks:

if self.board & mask == mask:

return -1

if shifted & mask == mask:

return 1

In spaces() function above, we use the popcount function from

gmpy as it is native and fast. Otherwise we

can use the function below as alternative:

def popcount(n):

return bin(n).count("1")

Secondly, we can consider memoize the minimax functions. In AI literature, this is called the transposition table. This is possible because our minimax function is deterministic and depends only on the board position and the player. It will be harder if the function also depends on the depth of the game tree (which is usually the case of chess) and the evaluation result is not deterministic (e.g., depends on some heuristic or some guesswork involved). Simple as this can greatly improve performance even on a full game tree search:

CACHE = {}

COUNT = 0

def simple_minimax(board, player);

"""player to move one step on the board, find the minimax (best of the worse case) score"""

# check cache for quick return

if (board.board, player) in CACHE:

return CACHE[(board.board, player)]

global COUNT

COUNT += 1

opponent = -player

value = evaluate(board)

if value is not None:

return value # exact score of the board

# possible opponent moves: The worse case scores in different options

candscores = [simple_minimax(b, opponent) for b in [board.place(r, c, player) for r, c in COORDS] if b]

# evaluate the best of worse case scores

if player == 1:

value = max(candscores)

else:

value = min(candscores)

# save into cache

CACHE[(board.board, player)] = value

return value

Here we see why a bitboard is beneficial: It is much easier to use two integers

as the key to the dictionary CACHE. The performance improvement is significant:

O move after 7381 search steps:

| |

---+---+---

| | O

---+---+---

| |

X move after 0 search steps:

| | X

---+---+---

| | O

---+---+---

| |

O move after 0 search steps:

| | X

---+---+---

| | O

---+---+---

O | |

X move after 0 search steps:

X | | X

---+---+---

| | O

---+---+---

O | |

O move after 0 search steps:

X | O | X

---+---+---

| | O

---+---+---

O | |

X move after 0 search steps:

X | O | X

---+---+---

| X | O

---+---+---

O | |

O move after 0 search steps:

X | O | X

---+---+---

| X | O

---+---+---

O | | O

X move after 0 search steps:

X | O | X

---+---+---

| X | O

---+---+---

O | X | O

O move after 1 search steps:

X | O | X

---+---+---

O | X | O

---+---+---

O | X | O

Tied

Thirdly, there are some standard practice to improve alpha beta search. Two of them are the heuristic improvement and killer heuristic.

The heuristic improvement means to reorder the children of a node before doing the alpha beta search. Remember that alpha beta search checks one child node at a time and narrow the bounds iteratively. If we have the best option as the first child, it can make the pruning more often and thus faster in the search.

Killer heuristic is having a similar idea: If certain move caused pruning in the past, it is believed that the same move will cause pruning again in another similar position.

For the former, it is a bit of an art. Indeed, a lot of research have been done to find the better evaluation function for positions of a particular game. If we have a universally correct evaluation function that can tell whether one position is better than another, we do not even need to do a game tree search but rather, just pick the best next step every time according to this function. Fortunately tic-tac-toe is a game simple enough that we have such function:

def heuristic_evaluate(board):

"""heuristic evaluation from <http://www.ntu.edu.sg/home/ehchua/programming/java/javagame_tictactoe_ai.html>"""

score = 0

for mask in Board.masks:

# 3-in-a-row == score 100

# 2-in-a-row == score 10

# 1-in-a-row == score 1

# 0-in-a-row, or mixed entries == score 0 (no chase for either to win)

# X == positive, O == negative

oboard = board.board

xboard = oboard >> 9

countx = popcount(xboard & mask)

counto = popcount(oboard & mask)

if countx == 0:

score -= int(10**(counto-1))

elif counto == 0:

score += int(10**(countx-1))

return score

The latter do not need the great mind to craft such artistic function. We just

need to remember what caused the last cut-off. Research has shown that using

last two cut-off instead of one has a better performance (power of two random

choice?) Thus we can use a deque() to implement the memory.

These two techniques are implemented in the alpha beta search as below. We can

modify the condition on the if statements to turn on or turn off those

techniques:

KILLERS = deque()

def alphabeta(board, player, alpha=-float("inf"), beta=float("inf")):

"""minimax with alpha-beta pruning. It implies that we expect the score

should between lowerbound alpha and upperbound beta to be useful

"""

if False and "Use cache":

# make alpha-beta with memory: interferes with killer heuristics

if (board.board, player) in CACHE:

return CACHE[(board.board, player)]

global COUNT

COUNT += 1

assert player in PLAYERS

opponent = -player

value = evaluate(board)

if value is not None:

return value # exact score of the board (terminal nodes)

# minimax search with alpha-beta pruning

masks = filter(None, [board.check(r, c, player) for r,c in COORDS])

children = [(mask, board.place(mask)) for mask in masks]

if False and "Heuristic improvement":

# sort by a heuristic function to hint for earlier cut-off

children = sorted(children, key=heuristic_evaluate, reverse=True)

if "Killer heuristic":

# remember the move that caused the last (last 2) beta cut-off and check those first

# <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Killer_heuristic>

children = sorted(children, key=lambda x: x[0] not in KILLERS)

if player == 1: # player is maximizer

value = -float("inf")

for mask, child in children:

value = max(value, alphabeta(child, opponent, alpha, beta))

alpha = max(alpha, value)

if alpha >= beta:

KILLERS.append(mask)

if len(KILLERS) > 4:

KILLERS.popleft()

break # beta cut-off

else: # player is minimizer

value = float("inf")

for _, child in children:

value = min(value, alphabeta(child, opponent, alpha, beta))

beta = min(beta, value)

if alpha >= beta:

break # alpha cut-off

# save into cache

if "Use cache" == False:

CACHE[(board.board, player)] = value

return value

For the game as simple as tic-tac-toe, these improvements are, unfortunately, not significant in time saving. But it is proved to be effective in larger games like chess. The reason is that, the game tree of tic-tac-toe is shallow enough to make the overhead of extra work out weight their benefit. However, they are indeed obvious in making the number of nodes to search smaller. Below is the result of using only killer heuristic without memoization or heuristic improvement as in the code above. We reduced the nodes to search on first step from 30709 to 21667:

O move after 21667 search steps:

| |

---+---+---

| | O

---+---+---

| |

X move after 7169 search steps:

| | X

---+---+---

| | O

---+---+---

| |

O move after 1514 search steps:

| | X

---+---+---

| | O

---+---+---

O | |

X move after 532 search steps:

X | | X

---+---+---

| | O

---+---+---

O | |

O move after 121 search steps:

X | O | X

---+---+---

| | O

---+---+---

O | |

X move after 53 search steps:

X | O | X

---+---+---

| X | O

---+---+---

O | |

O move after 13 search steps:

X | O | X

---+---+---

| X | O

---+---+---

O | | O

X move after 4 search steps:

X | O | X

---+---+---

| X | O

---+---+---

O | X | O

O move after 1 search steps:

X | O | X

---+---+---

O | X | O

---+---+---

O | X | O

Tied

Principal variation search / NegaScout

There is yet another possible techniques to improve on alpha-beta pruning. Notice that alpha-beta pruning starts with a bound \([\alpha, \beta]\) on expected minimax value and whenever the searched value is out of this bound, the branch is pruned. So if we have a very tight bound, we can prune more often and the game tree to search will be smaller. This is the idea of principal variation search which also comes with other names including NegaScout or MTDF(n) algorithm. Strictly speaking they should have some subtle difference in the implementation but share the same philosophy.

So when we use this technique on a node of a game tree, we first check the first child node for a value using the ordinary alpha-beta search. Then on the subsequent child nodes, we check their with a zero-window. A zero-window will cause the branch to be pruned quickly or failed-high on a maximizer node (or failed-low on a minimizer node). At this latter case, we are quite sure to find a tighter bound and perform alpha-beta search again.

This, again, pose some overhead to the game tree search as we might need to search the child node twice: once with zero window and once with a larger alpha-beta window. The implementation is as follows but it turns out, not worthwhile (either in terms of number of nodes searched or the time taken) in a shallow game tree like tic-tac-toe.

def negascout(board, player, alpha=-float("inf"), beta=float("inf")) -> float:

"""minimax with alpha-beta pruning. It implies that we expect the score

should between lowerbound alpha and upperbound beta to be useful

"""

global COUNT

COUNT += 1

assert player in PLAYERS

opponent = -player

value = evaluate(board)

if value is not None:

return value # exact score of the board (terminal nodes)

# negascout with zero window and alpha-beta pruning

masks = filter(None, [board.check(r, c, player) for r,c in COORDS])

children = [(mask, board.place(mask)) for mask in masks]

# first child: alpha beta search to find value lbound/ubound

bound = negascout(children[0][1], opponent, alpha, beta)

if player == 1: # player is maximizer, bound is lbound

if bound >= beta:

return bound # beta cut-off

# subsequent children: zero window on lbound

for mask, child in children[1:]:

t = negascout(child, opponent, bound, bound+1)

if t > bound: # failed-high, tighter lower bound found

if t >= beta:

bound = t

else:

bound = negascout(child, opponent, t, beta) # re-search for real value

if bound >= beta:

return bound # beta cut-off

else: # player is minimizer, bound is ubound

if bound <= alpha:

return bound # alpha cut-off

# subsequent children: zero window on ubound

for mask, child in children[1:]:

t = negascout(child, opponent, bound-1, bound)

if t < bound: # failed-low, tigher upper bound found

if t <= alpha:

bound = t

else:

bound = negascout(child, opponent, alpha, t) # re-search for real value

if bound <= alpha:

return bound # alpha cut-off

return bound

Monte-Carlo tree search

Above we discussed the alpha-beta search with a different variations. We made various attempt to narrow down the scope of search on the game tree.

There is another way to save time on the search, based on a totally different idea. If we are on a node and a particular player’s turn. We still want to minimize our maximum loss. We can pretend, on each child node, how the game might proceed until the end by playing random moves and repeat for multiple times and count how often we will win or loss. Then we pick the next step that gave us least percentage of loss. This is a Monte-Carlo search on the game tree. The code is surprising simple:

def mcts(board, player):

"""monte carlo tree serach

Returns:

the fraction of tree search that the player wins

"""

N = 500 # number of rounds to search

count = 0 # count the number of wins

for _ in range(N):

step = Board(board.board)

who = player

while step.spaces():

r, c = random.choice(COORDS)

nextstep = step.place(r, c, who)

if nextstep is not None:

who = -who # next player's turn

step = nextstep

if step.won(): # someone won

break

if step.won() == player:

count += 1

return count / N

def play():

"auto play tic-tac-toe"

minimizer = True

game = Board()

# loop until the game is done

while not game.won():

player = PLAYERS[minimizer]

opponent = PLAYERS[not minimizer]

candidates = [(b, mcts(b, opponent)) for b in [game.place(r, c, player) for r, c in COORDS] if b]

if not candidates:

break

random.shuffle(candidates)

# find best move: min opponent's score

game, score = min(candidates, key=lambda pair: pair[1])

# print board and switch

minimizer = not minimizer

print()

print("%s move on score %f:" % (symbol(player), score))

print(game)

winner = game.won()

print()

if not winner:

print("Tied")

else:

print("%s has won" % symbol(winner))

The while loop in function mcts() will stop only when the game end. The

function counts how many times the player wins among the N repetitions. When

we play with MCTS, we try to minimize the percentage of opponent win – and we

do not have the distinction of maximizer or minimizer nodes any more.

In a small game tree of tic-tac-toe, MCTS performs well:

O move on score 0.188000:

| |

---+---+---

| O |

---+---+---

| |

X move on score 0.628000:

| |

---+---+---

| O |

---+---+---

| | X

O move on score 0.154000:

| |

---+---+---

| O | O

---+---+---

| | X

X move on score 0.508000:

| |

---+---+---

X | O | O

---+---+---

| | X

O move on score 0.000000:

| |

---+---+---

X | O | O

---+---+---

O | | X

X move on score 0.338000:

| | X

---+---+---

X | O | O

---+---+---

O | | X

O move on score 0.000000:

| | X

---+---+---

X | O | O

---+---+---

O | O | X

X move on score 0.000000:

| X | X

---+---+---

X | O | O

---+---+---

O | O | X

O move on score 0.000000:

O | X | X

---+---+---

X | O | O

---+---+---

O | O | X

Tied

Of course, playing the game randomly may not be a good idea. If we know how our opponents might play each move with a probability, we can gauge the probability of move accordingly. This is indeed the idea of modern AI of game playing and finding such probability vector is the state of the art. But the above is pretty much all we have for the last century.

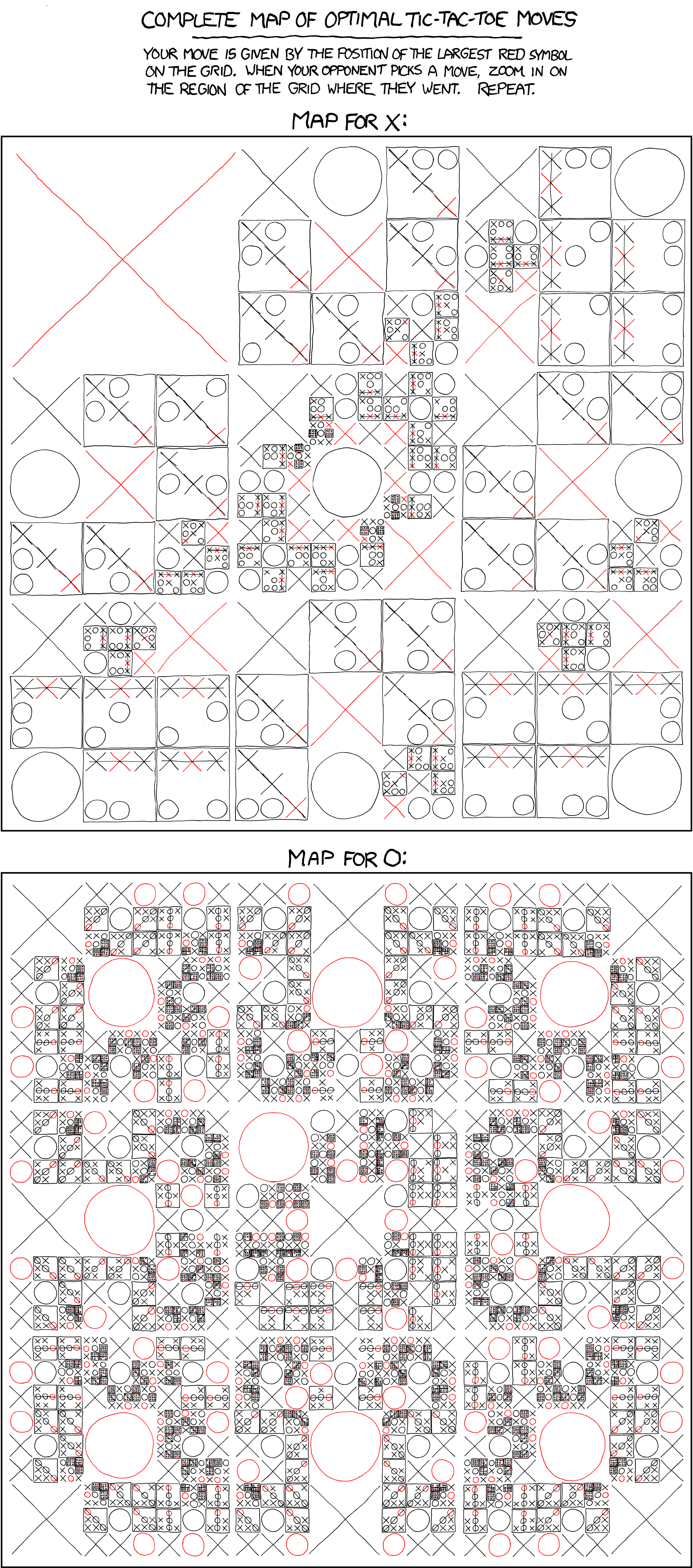

Tic-tac-toe is never an interesting problem of research. Even xkcd can give you a solution on how to play the game:

All code above are in the following repository: https://github.com/righthandabacus/tttai